MLK & Malcolm X

April 3rd, 2008

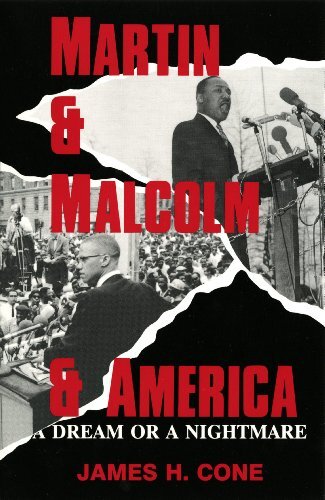

James H. Cone’s Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare is a quality analysis of the ideas of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, but not one without flaws. Cone’s central argument is that Martin and Malcolm were not as opposite as is commonly held and that we should really believe in elements of both men’s philosophy. Cone also correctly critiques both men for their classism and sexism. He clearly shows how Malcolm and King’s ideas changed over time and became closer in the last years of their lives. Though Cone’s work is more right than wrong, his nationalist-integrationist perspective is too simplistic and he has a tendency to reify America.

Cone does an excellent job showing how both Malcolm & King’s ideas changed over time. In the last year and a half of his life Malcolm was kicked out of the Nation of Islam and his philosophy began moving closer to King’s integrationist philosophy. Malcolm became less hostile towards the other wings of the black liberation movement and tried to forge a broader unity among African-Americans.

King’s philosophy also changed in the later years of his life, beginning with his receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize when he had an opportunity to observe democratic socialism in Scandinavia. Although King had been quietly anti-capitalist since graduate school, as the sixties wore on he became increasingly focused on issues of economic justice, eventually lead the Poor People’s Campaign. His position also moved closer towards Malcolm’s position.

Cone divides thinkers along an integrationist-nationalist spectrum. According to him, African-American intellectuals can be classified by their response to the question, “What ... am I? Am I an American or am I a Negro? Can I be both?” (p. 3) Cone argues that those who answer “yes” are integrationists while those who answer “no” are nationalists. He further argues that most thinkers believe in elements of both and that there are few pure nationalist or pure integrationist thinkers.

Cone’s integrationist-nationalist division is limited because it privileges national and racial identity above other identities. The same question Cone asks about being American and black could be asked of any other two identities. He does not give any reason why, for example, gender and class should not be subjected to a similar question.

A bigger problem with Cone’s nationalist-integrationist paradigm is that it ignores positions that do fit within an integrationist-nationalist spectrum. For example, many Communists and other Marxists tend to put their identity as workers above either national or racial identities, and might well reject being either American or “Negro.” To paraphrase Karl Marx in the Communist Manifesto, “workers of the world have no country.” Since Communists were a major part of the civil rights movement during the 1930s, this incompatibility of Communism with the integrationist-nationalist spectrum is / a problem for Cone’s paradigm.

Cone also tends to reify America. Cone has a tendency to portray America as a thing, as he does when he states, “both philosophies [black nationalism & integrationism] were needed if America was going to come to terms with the truth of the black experience.” (p. 16) “America” doesn’t actually exist. It is not a thing or a life form with needs, but an imagined community. There is an American government, a large number of people who consider themselves Americans, and multiple ideologies purporting to be “American” but to talk of “America” in the abstract as if it were a thing obscures reality. Who, precisely, is it that needs Black Nationalism & integrationism? Cone does not clearly specify. While it is true that that element of both King & Martin’s philosophies are valid, including elements of black nationalism & integrationism, it does not necessarily follow that some unspecified “America” (whoever that is) needs it.